The Lady Elgin Disaster, Part 2

There were many people on the bluffs watching for the Lady Elgin to pass the night of September 7-8, 1860. One of the watchers was Henry “Hank” Mower who lived in Highwood, Lake, Illinois, “just at the edge of a bit of woods which joins on the south the clump of tree which rise above the graves of the Lady Elgin dead.” Highwood is located in Moraine Township, between Chicago and Kenosha. When he was asked if “any of the Lady Elgin dead were buried in the woodland cow pasture” Mower replied, yes, “with my own hands—for I am a carpenter by trade—I made four coffins for four of the unidentified dead which the waves tossed ashore after the wreck of the steamer thirty-nine years ago. I helped bury all four.” He continued his tale: “I was on the beach immediately after the wreck of the Lady Elgin. You see, it was cut down a good ways north of here, but drifted south some miles and the great majority of the survivors reached shore near Winnetka, and it was there also that most of the bodies were washed ashore. I saw the boat go by the old lighthouse on the night it went down. It was a big steamer, and big steamers were not as plentiful in those days as they are now; moreover, the Lady Elgin was the most famous boat on the great lakes. It was quite the common thing for the people along the shore to go to the bluffs to see it go by. “On that night it was brilliantly lighted, for it had many excursionists on board. After watching it pass I went away from the bluffs, but heard of the wreck a few hours afterward and went sought to that point of the beach where the people were gathered. The sight was something awful. On what appeared to me to be the roof of the pilothouse there were floating certainly more than forty people. All at once a give wave engulfed them and they were all lost.” “For days afterward bodies continued to be washed up by the sea on the beach just below the lighthouse.” 1]

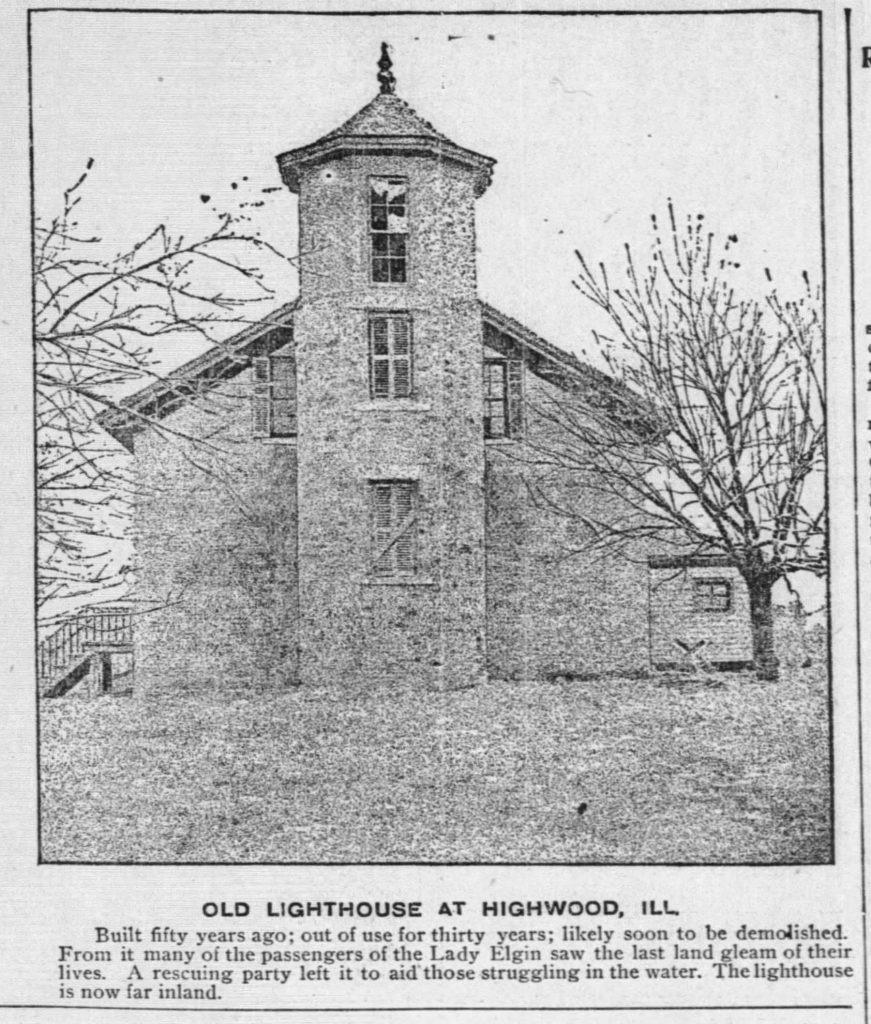

It was here at the lighthouse that the townspeople lay the bodies that had been recovered from the shore. “Underneath the stairway which mounted to the stone floor supporting the great lamp there lay the bodies of many of the dead, and there grief-stricken people by the hundreds viewed the grewsome [sic] line of faces showing above the white sheets to see if the loved one sought might not be there. From this place were carried many of the unidentified dead to be buried in now almost unknown graves.” 2]

Owen Monahan was the lighthouse keep. The night of September 8th he, and several men who were with him, were looking for the passing of the Lady Elgin. “They watched its lights until it was well near Waukegan, and then all at once they seemed to know, half by intuition, that something was wrong. The vessel soon drifted back helplessly across the line of their vision as rapidly, perhaps more rapidly than but a span of time before it had passed proudly northward. Monahan left the light in charge of an attendant, and with some of his fellow-watchers started south, following the still burning lights of the steamer. They were among the hardest workers at the scenes of rescue where rescue was possible.” 3]

“When the stricken Lady Elgin had drifted to a point nearly opposite Winnetka it began to go to pieces. The people flocked near and far to rescue. Two students Spencer and Combs, from the Garrett Biblical Institute at Northwester University, “with ropes around their waists, rushed into the waves and rescued many persons. On one occasion, Spencer saw that he could not reach a struggling person whom he was seeking because of the shortness of the rope, he bade them cast him loose and after a hard fight succeeded in saving two people…” Due to his heroic efforts, he saved at least 17 lives that night, and at the cost of his own health. He would be pulled in with each survivor, and would immediately dive in and rescue another, and this effort made a lasting effect on him, as he was a semi-invalid for the rest of his life. “After the wreck men whom the newspapers of the day characterized as ‘devils and beasts’ were found rifling the bodies of the dead. Others broke open casks of liquor which the waves had thrown ashore and became a mad as the elements.” 4]

There are many other first hand accounts of brave rescues, and heroic measures to make it to shore, but I feel that these few tales gives the flavor of what happened that awful night 160 years ago.

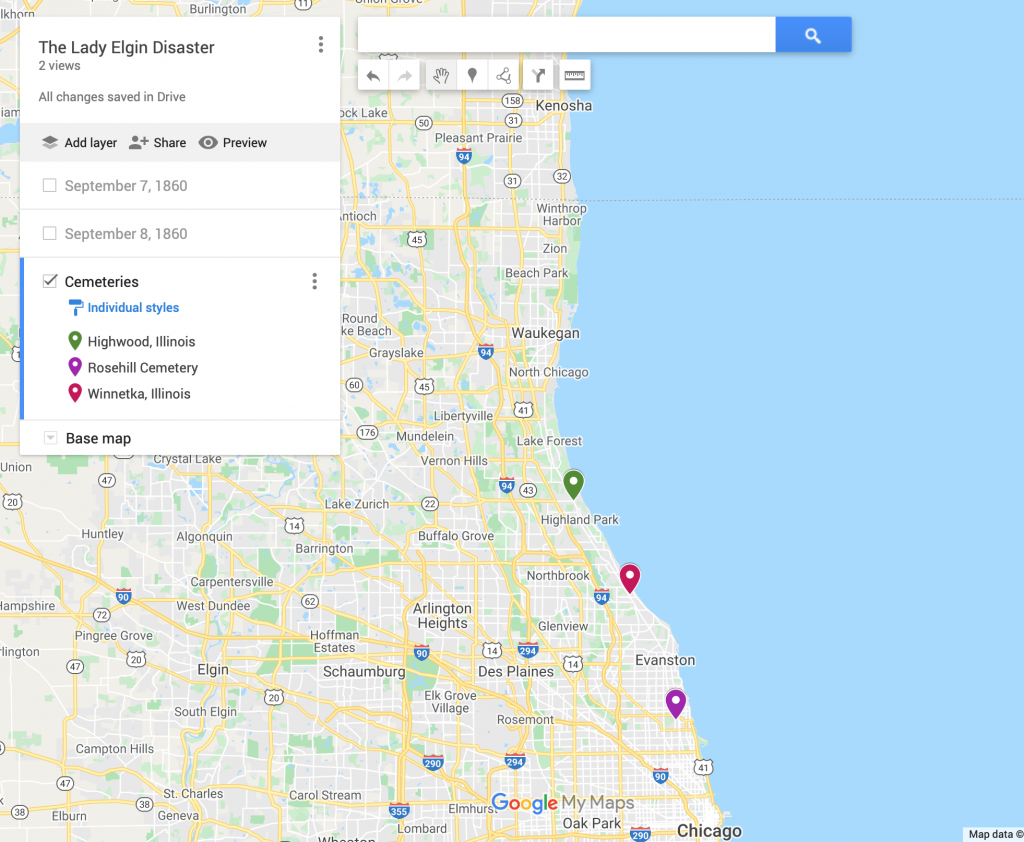

The lake continued to let go of the passengers well into December, when two more bodies were discovered washed onto the shore near St. Joseph, Berrien Co., Michigan. 5] We can only hope that they were given proper burial, as identification would have been almost impossible due to the “very advanced stage of decomposition.” Two cemeteries were noted in those early newspapers as having graves for the unidentified, Rosehill Cemetery, and the small cemetery at Highwood, Illinois.

The cemetery at Highwood, Lake, Illinois was soon “Forgotten and neglected in a desolate section of a half woodland, half meadowland pasturage, in a remote corner of the little Village of Highwood, Ill., sleep some—no one seems to know just how many—of the unidentified dead who gave up their lives with the loss of the steamer Lady Elgin..” “Due east as the crow flies, within the half mile, stands a battered, crumbling lighthouse with its sightless eyes directed seaward. Once, years in the past, they glinted with fire, and one beam, shot out on an inky night, was the last land light which most of the luckless ones on the Lady Elgin ever saw in life.” 6] Adam Selzer wrote a blog post about the cemetery in his blog: “Adam Selzer’s Mysterious Chicago Tours, September 3, 2015.” He states that this lost cemetery had been located by the Highwood Historical Society, and documented in their newsletter. Unfortunately the link to this newsletter is long dead. This cemetery can also be found on Find A Grave, Cemetery ID: 2676413.

Rosehill Cemetery became another resting spot for the unrecognized dead. “From the elevated slope at Rose Hill, where those unknown dead are buried, could be seen out beyond the trees that fringe the lake shore, the calm blue waters, in the very spot where the Lady Elgin and her victims went down in the seething angry waves.” The Chicago Tribune wrote in 1861: “Twenty-seven bodies, after long and hopelessly awaiting recognition and recovery by friends, were here tenderly buried side by side, in a tract set apart by the Directors of Rose Hill.” “Here they rest. Not undistinguished, for among the Cemetery records are treasured the shreds of information and description, the which even now, or years hence, may furnish a clue to inquiring friends, and by this record the resting place of any one of the bodies may be pointed out. There is little hope now that of those poor remains, which were washed up stark and ghastly from the too late relenting waves, any will ever be removed to be gathered to kindred dust. The neatly turfed lot, with its gravelled walks and and [sic] blooming flowers, tells of the care and attentions befitting the grave of the stranger, and in due time a proper memorial will be raised to mark the spot where repose these unknown dead, and to commemorate the calamity which one year ago to-day fell like a pall upon so many hearts and homes.” 7] Sadly, a search of Rosehill’s website makes no mention of these 27 unknown victims.

The Lady Elgin is also remembered in Milwaukee, where a Wisconsin Historical Marker, number 327, named: Sinking of the Lady Elgin was erected by the Wisconsin Historical Society in 1996. The marker is mounted on the wall of 102 North Water Street, at the corner of Water and East Erie Street.

Calvary Cemetery in Milwaukee has many memorials dedicated to family members lost on the Lady Elgin. Monuments, called cenotaphs, have the inscription included: “lost on the Lady Elgin” as a memorial for these people, as they are not actually buried in the cemetery. Many memorials can be found in Blocks 5, 6, and 7, a majority in block 6.

Following the disaster, media coverage slowed, yet the Lady Elgin was not forgotten. In March 1861 a song titled “Lost on the Lady Elgin” was written by Henry Clay Work, which became a national best-seller, and it can still be heard today on YouTube. Although survivors gathered annually near the date of the tragedy, they did not formally create a society until September 7, 1889, when the Lady Elgin Survivors Society was formally formed. Reunions of the survivors were held until 1907. One notable reunion was held in September 1891. Survivors participated in an excursion from Milwaukee to Winnetka, to walk the beach where many had been saved, and many of the lost had been recovered. On the beach north of Winnetka was found a thirty-foot piece of the wreck, half buried in the sand. Each of the survivors received a piece of the hull as a souvenir.

The tragedy that was the loss of the Lady Elgin is a much deeper story than I have written here. There is an important political component to the reason that so many from Milwaukee had travelled to Chicago that day. There is also the sad story of the finding of the sunken Lady Elgin, and the court battle over who owned the rights to the wreck sitting at the bottom of the lake. Others have written about this important side of the tragedy. My goal was to reflect on the Cook family, and the toll it took on all of them to lose a mother and a sister, and for Jacob to have survived, badly bruised, and grieving for the fact that he could not save his mother and sister. So much was taken from them that tragic day, yet the children of Jane McGarvy Cook rose above it, and all of them became well respected, well liked citizens. On that day in 1860, Jane was 49 years old, she had been married to William Cook for 28 years. She was the mother of 12 children, including two sets of twins. Her oldest child was 27, her youngest was just eight years old.

In 1910 Col. Watrous wrote for The Chilton Times: “No pen can describe the grief, shock and distress in the Cook household when the awful news reached it. The very day that the happy flock in the Stockbridge home was expecting the return of the absent ones the terrible news came instead. The father was utterly crushed. The great heart, strong intellect, the master mind, the loving, successful planner and leader, the pilot of the interesting family was no more; her going meant final disaster to the father, irreparable loss to nine [sic] surviving boys and girls.

There was no money to meet payments on the six farms and they were lost. But little was saved on the homestead. The wreck of the Lady Elgin seems to have wrecked the whole family, yet only for a short time did it seem so.”8]

Lady Elgin books in my library:

~ Charles M. Scanlan, The Lady Elgin Disaster, September 8, 1860, (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Charles M. Scanlan, 1928).

~ Pete Caesar, The Lady Elgin is Down, revised 1999 ed. (Green Bay, Wisconsin: Great Lakes Marine Research, 1981).

~ Valerie Van Heest, Lost on the Lady Elgin, first ed. (United States of America: In-Depth Editions, 2010).

Notes:

- “Graves of Lady Elgin Dead Desecrated,” The Chicago Sunday Tribune, 26 May 1899, Sunday, p. 1, part 4; Editorial Sheet; digital images, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com : accessed 4 Jul 2018).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “More Bodies Found,” The St. Joseph Traveler, 5 Dec 1860, Wednesday, p. 3, col. 1; digital images, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com : accessed 22 Jul 2018).

- “Graves of Lady Elgin Dead Desecrated,” The Chicago Sunday Tribune, 26 May 1899, Sunday, p. 1, part 4; Editorial Sheet; digital images, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com : accessed 4 Jul 2018).

- “The Unknown Dead,” The Chicago Tribune, 7 Sep 1861, Saturday, p. 4, col. 2; digital images, Newspapers.com (www.newspapers.com : accessed 6 Jul 2018).

- “A Memorable Time ~ Old Day-Events Are Recalled ~ Lieut. Col. J. A. Watrous of Milwaukee Writes for The Times of the Coming of the Cook Family to Stockbridge,” (Chilton) The Chilton Times, 19 Mar 1910, Saturday, p. 1, col. 2.